政府が破綻金融機関などから買い取った不良債権の回収額が今年3月末時点で9兆7938億円となり、1996年以降の買い取り総額(9兆7775億円)を上回ったことが分かった。旧日本長期信用銀行と旧日本債券信用銀行の不良債権で回収額が買い取り額を4700億円余り上回ったことなどが背景。回収の実務を担う整理回収機構(RCC)は残る貸出先企業への返済要請などを今後も継続するが、不良債権買い取りによる追加損失は回避された格好だ。

政府は破綻した銀行や信用金庫、信用組合を受け皿となるスポンサーに引き継ぐ際に、預金保険機構を通じて破綻金融機関が抱える不良債権を買い取ってきた。

96年以降に取得

金融機関の再生を後押しする狙いで、96年以降、約160社からの買い取り総額は簿価ベースで9兆7775億円にのぼった。

個別の買い取り額については、それぞれの金融機関の引当金の状況や回収可能性を検討。金融機関の帳簿上の金額を下回る水準で設定されたため、貸出先からの返済が着実に進めば、回収超過が生じる仕組みになっている。預保機構の傘下のRCCは2010年3月までに融資の返済や債権の流動化などで、9兆7938億円を回収。買い取り簿価を163億円上回った。

買い取り額と回収額の内訳をみると、旧長銀(現新生銀行)と旧日債銀(現あおぞら銀行)では1兆1798億円の買い取り簿価に対し、回収額が1兆6545億円となった。ただ両行からは持ち合い株式なども2兆9421億円買い取っており、この回収は1兆7194億円と6割弱にとどまっている。

また不良債権処理を加速するために、破綻していない金融機関から買い取った債権3533億円の回収額は1.9倍の6699億円に達する。

公的資金は9割

バブル崩壊後の不良債権処理に苦しむ金融機関に対する支援では、政府は資本不足を補うために98年以降に公的資金も注入した。金融機能安定化法や早期健全化法、預金保険法などに基づく公的資金の注入総額(金融機能強化法は除く)は簿価ベースで12兆3869億円。今年8月末時点の回収総額は11兆3514億円で、こちらの回収率は9割を超えた。不良債権問題は、買い取りが始まった96年から14年もの期間を経て、ようやく「出口」に近づきつつあるといえる。

もっとも、政府は金融不安の高まりを受けて96年4月に、預金の払戻保証額を元本1千万円とその利息までとするペイオフを凍結。国民の動揺を抑えるために破綻金融機関の預金を全額保護し、19兆円弱を戻ってこない資金として拠出している。

source: nikkei

不良債権[ bad [nonperforming] loans ]

金融機関が融資した後、約束通りに返済されなくなった、あるいは返済の見通しが立たない貸出金のこと。金融機関のバランスシートに、利益を生まない資産として計上されている。融資先が倒産した破綻先債権、金融支援先向けの要管理先債権などが代表例。

預金保険[ deposit insurance ]

銀行の経営が不振になったり信用恐慌が起きたりすると、預金が焦げ付いてしまう恐れがあるが、そのようなことのないよう預金にかける保険。保険料は預金という財産を受け入れる側(金融機関)が保険機関(日本の場合は預金保険機構)に支払うので、預金者は債権の一定部分の安全性を保つことができる。2005年4月のペイオフ全面解禁で、全額保護が続く決済用預金については普通預金に比べて高く設定された。

引当金[ allowance ; provision ; reserve ]

将来予想される特定の支出や損失に備えるために企業が積み立てるお金のこと。貸出金が返ってこないことに備えて計上する貸倒引当金が最もポピュラーな引当金。年金の支出に備えた引当金などもある。

金融機能強化法[ Financial Function Early Strengthening Law ]

金融機関の申請に基づき、国が公的資金を資本注入する枠組みを定める。2004年6月の国会で成立し、2兆円の注入枠を確保した。金融危機の恐れがあるときに発動する預金保険法に対し、危機の兆しがなくても経営基盤の強化を望む金融機関の要請で資本注入できる。政府はこの制度をテコに地域金融機関の再編を進め、金融システムを安定させる効果を期待している。08年12月に改正法が成立し、注入枠は12兆円に増えた。12年3月末までの時限措置。

単独で円売り介入 成長政策実行、時間買う

政府・日銀が6年半ぶりの円売り介入に踏み切った。日本が直面するデフレ圧力と円高の悪循環をとりあえず押しとどめる姿勢を示したといえる。だが、世界経済の構造が大きく変化するなかで、日本が「買った時間」は長くはない。

菅改造内閣は円高に有効な策が打てるか(15日、首相官邸を出る野田財務相)

先週初め。財務省の玉木林太郎財務官はパリにいた。円売り介入の数日前。関係者は「一切答えられない」と口を閉ざすが、介入の事前了解を欧米から取り付けるべく動いていた可能性が高い。

13日、スイス・バーゼル。国際決済銀行(BIS)で開かれた主要国中銀総裁会議に白川方明総裁ら日銀首脳が出席していた。首脳らはここでも円高に苦しむ日本の現状を説明した形跡もある。

「協力してくれとは言わないが、黙認してほしい」。政府・日銀関係者と海外当局者の折衝は、介入が日本単独とならざるを得ない厳しい現実を映し出していた。

だが、日本が直面する課題は介入で解決できるほど甘くはない。同じような円高だった15年前と比べても、世界経済の構造変化は著しい。

通貨安競争誘う

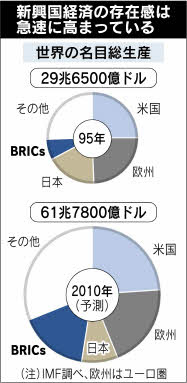

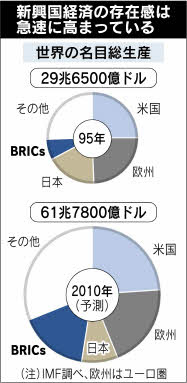

国際通貨基金(IMF)によると2010年の世界の名目国内総生産(GDP、ドル換算)のうちBRICs(ブラジル、ロシア、インド、中国)の比率は16%強。1995年に比べて10ポイント近くも増えた。

08年9月のリーマン・ショック後、この傾向は一段と鮮明だ。新興国と対照的に米国は過剰消費のツケ、欧州は金融システム不安、日本は構造的なデフレ圧力にあえぐ。

世界経済の構造が変化するなかで、日本の円売り介入は国際社会の「通貨安競争」を助長するリスクをはらむ。

「あらゆる国にとって為替安定は重要だ」。中国の国営メディアは日本の介入を大きな扱いで報道した。日本に理解を示しつつ、人民元売り・ドル買い介入を正当化する狙いが垣間見えた。

中国だけではない。アジア諸国は自国通貨売り・ドル買い介入を繰り返し、外貨準備が急増している。1年前と比べた6月末残高は中国が15.1%増の2兆4543億ドル、台湾が14.1%増の3624億ドル、韓国が18.3%増の2742億ドル。リーマン・ショック前と比べると、韓国ウォンは日本円に対して46%、人民元は22%も減価した。

「(通貨安)ゲームを黙って観戦しているわけにはいかない」。ブラジルのマンテガ財務相は15日、日本の介入を批判し、レアル高阻止に向け強い決意を示した。

強いドル唱えず

輸出主導で新興国市場を獲得し、リーマン・ショックからの回復を目指す米オバマ政権は、15年前に当時のルービン財務長官が唱えたような「強いドル」をもはや口にしない。日本が介入した翌16日の米下院歳入委員会公聴会。「対等な競争環境をどうやって確保するか。中国だけの問題ではない」。ガイトナー現財務長官は強調した。

「近隣諸国に配慮した政策協調と通貨切り下げの抑制」。09年4月、20カ国・地域(G20)首脳会議の声明はこううたった。だが、いまの世界はG20声明とは異なる方向に動くリスクを抱えているようにみえる。

今回の日本の介入はそんな世界のリアリズムに呼応し、円高とデフレの負の相乗効果に歯止めをかけたとの評価もある。だが、「介入は一時しのぎ。成長力を引き上げる政策こそが重要だ」と日銀関係者は言う。

法人税制の見直し、サービス業の規制緩和・生産性向上、新規ビジネスの育成……。必要な施策を巡る議論は出尽くしている。後は、いつ何を実行するか。17日に発足した菅直人改造内閣が手をこまぬいていれば、市場は政権の本気度を再び試す動きに出るに相違ない。

source: nikkei

.

菅改造内閣は円高に有効な策が打てるか(15日、首相官邸を出る野田財務相)

先週初め。財務省の玉木林太郎財務官はパリにいた。円売り介入の数日前。関係者は「一切答えられない」と口を閉ざすが、介入の事前了解を欧米から取り付けるべく動いていた可能性が高い。

13日、スイス・バーゼル。国際決済銀行(BIS)で開かれた主要国中銀総裁会議に白川方明総裁ら日銀首脳が出席していた。首脳らはここでも円高に苦しむ日本の現状を説明した形跡もある。

「協力してくれとは言わないが、黙認してほしい」。政府・日銀関係者と海外当局者の折衝は、介入が日本単独とならざるを得ない厳しい現実を映し出していた。

だが、日本が直面する課題は介入で解決できるほど甘くはない。同じような円高だった15年前と比べても、世界経済の構造変化は著しい。

通貨安競争誘う

国際通貨基金(IMF)によると2010年の世界の名目国内総生産(GDP、ドル換算)のうちBRICs(ブラジル、ロシア、インド、中国)の比率は16%強。1995年に比べて10ポイント近くも増えた。

08年9月のリーマン・ショック後、この傾向は一段と鮮明だ。新興国と対照的に米国は過剰消費のツケ、欧州は金融システム不安、日本は構造的なデフレ圧力にあえぐ。

世界経済の構造が変化するなかで、日本の円売り介入は国際社会の「通貨安競争」を助長するリスクをはらむ。

「あらゆる国にとって為替安定は重要だ」。中国の国営メディアは日本の介入を大きな扱いで報道した。日本に理解を示しつつ、人民元売り・ドル買い介入を正当化する狙いが垣間見えた。

中国だけではない。アジア諸国は自国通貨売り・ドル買い介入を繰り返し、外貨準備が急増している。1年前と比べた6月末残高は中国が15.1%増の2兆4543億ドル、台湾が14.1%増の3624億ドル、韓国が18.3%増の2742億ドル。リーマン・ショック前と比べると、韓国ウォンは日本円に対して46%、人民元は22%も減価した。

「(通貨安)ゲームを黙って観戦しているわけにはいかない」。ブラジルのマンテガ財務相は15日、日本の介入を批判し、レアル高阻止に向け強い決意を示した。

強いドル唱えず

輸出主導で新興国市場を獲得し、リーマン・ショックからの回復を目指す米オバマ政権は、15年前に当時のルービン財務長官が唱えたような「強いドル」をもはや口にしない。日本が介入した翌16日の米下院歳入委員会公聴会。「対等な競争環境をどうやって確保するか。中国だけの問題ではない」。ガイトナー現財務長官は強調した。

「近隣諸国に配慮した政策協調と通貨切り下げの抑制」。09年4月、20カ国・地域(G20)首脳会議の声明はこううたった。だが、いまの世界はG20声明とは異なる方向に動くリスクを抱えているようにみえる。

今回の日本の介入はそんな世界のリアリズムに呼応し、円高とデフレの負の相乗効果に歯止めをかけたとの評価もある。だが、「介入は一時しのぎ。成長力を引き上げる政策こそが重要だ」と日銀関係者は言う。

法人税制の見直し、サービス業の規制緩和・生産性向上、新規ビジネスの育成……。必要な施策を巡る議論は出尽くしている。後は、いつ何を実行するか。17日に発足した菅直人改造内閣が手をこまぬいていれば、市場は政権の本気度を再び試す動きに出るに相違ない。

source: nikkei

.

Labels: Introduction

Japan Economy

Wall Street’s Profit Engines Slow Down

September 19, 2010

By NELSON D. SCHWARTZ

Inside the great investment houses on Wall Street, business has taken a surprising turn — downward.

Even after taxpayer bailouts restored bankers’ profits and pay, the great Wall Street money machine is decelerating. Big financial institutions, including commercial banks, are still making a lot of money. But given unease in the financial markets and the economy, brokerages and investment banks are not making nearly as much as their executives, employees and investors had hoped.

After an unusually sharp slowdown in trading this summer, analysts are rethinking their profit forecasts for 2010.

The activities at the heart of what Wall Street does — selling and trading stocks and bonds, and advising on mergers — are running at levels well below where they were at this point last year, said Meredith Whitney, a bank analyst who was among the first to warn of the subprime mortgage disaster and its impact on big banks.

Worldwide, the number of stock offerings is down 15 percent from this time last year, while bond issuance is off 25 percent, according to Capital IQ, a research firm. Based on these trends, Ms. Whitney predicts that annual revenue from Wall Street’s main businesses will drop 25 percent, to around $42 billion in 2010, from $56 billion last year.

While the numbers will not be known until after the third quarter ends and financial companies begin reporting earnings in October, the pace of trading this summer was slow even by normal summer standards. Trading in shares listed on the New York Stock Exchange was down by 11 percent in July from 2009 levels, and August volume was off nearly 30 percent.

“What’s happened in the third quarter is that after a very slow summer, people expected things to come back,” said Ms. Whitney. “But they haven’t, and the inactivity is really squeezing everyone.”

The downward slide on Wall Street parallels a similar shift in the broader economy, which has slowed considerably since showing signs of a nascent recovery this spring. And if banks come under pressure, all but the safest borrowers may struggle to get loans.

With less than two weeks to go in the third quarter, companies will be hard-pressed to fulfill earlier, more optimistic expectations.

“It’s like the marathon: if you’re five miles behind, you can’t make that up in the last 10 minutes of the race,” said David H. Ellison, president of FBR Fund Advisers, a money management firm that specializes in financial companies. Many banks are barely scraping by in traditional Wall Street business.

As a result, executives, portfolio managers and analysts say that even the mighty Goldman Sachs, which posted a profit every day for the first three months of the year, is unlikely to deliver the kind of profit growth that investors have come to expect.

Keith Horowitz, a bank analyst at Citigroup, said he expected Goldman Sachs to earn $7.8 billion in 2010, a 35 percent decline from the $12.1 billion it made last year.

The drop in trading translates into lower commissions for brokerage firms, as well as a weaker environment for underwriting initial public offerings and other stock issues, traditionally a highly lucrative niche.

Banks are also scaling back on making bets with their own money — known as proprietary trading — another huge profit source in recent years that will soon be forbidden under terms of the financial reform legislation passed by Congress this summer.

Indeed, analysts have finally started to bring their forecasts in line with the new reality. On Sept. 12, Mr. Horowitz reduced his estimates for third-quarter profits at Goldman and Morgan Stanley.

Mr. Horowitz had predicted Goldman would make $1.75 billion in the third quarter, or $3 a share; he now expects Goldman’s profit to total $1.34 billion, or $2.30 a share. For Morgan Stanley, his revision was even steeper, with earnings expectations revised downward to $140 million, or 10 cents a share, from $726 million, or 53 cents a share.

Mr. Horowitz’s estimates are considerably lower than the consensus among analysts who track the two companies. If the other analysts revise their estimates closer to his, they would put pressure on the shares.

One of the rare bright spots for Wall Street recently has been the issuance of junk bonds, as ultra-low interest rates encourage investors to seek out riskier debt that carries a higher yield. But that will not be enough to offset the weakness elsewhere, said one top Wall Street executive who insisted on anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly for his company, and because final numbers would not be tallied until the end of the month.

To make matters worse, he said, many Wall Street firms increased their work forces in the first half of the year, before the mood shifted and worries of a double-dip recession arose. If activity remains anemic, firms could soon begin cutting jobs again.

“I think the summer was horrible for everyone, and no one expected it to be as bad as it was,” he said. “It’s coming back a little bit in September but nowhere near enough to make up for what happened in July and August.”

The profit picture is brighter for diversified companies like JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America, which have larger commercial and retail banking operations in addition to their Wall Street units, but some analysts say earnings expectations for them could come down as well.

“Estimates still seem a little high, and the revenue story for all the banks is not a good one,” said Ed Najarian, who tracks the banking sector for ISI, a New York research firm.

With interest rates plunging, banks are making less off their interest-earning assets like government bonds and other ultra-safe securities. At the same time, demand for new loans remains weak.

One wild card will be the credit card portfolios at major banks like JPMorgan, Bank of America and Citigroup. As delinquencies ease, Mr. Najarian said, credit losses are likely to decline. That trend helped earnings at JPMorgan in the second quarter, and could be crucial again in the third quarter.

Ms. Whitney says the gloomy short-term predictions foreshadow a series of lean years in the broader financial services industry.

Indeed, she said the Street faced a “resizing” not seen since the cutbacks that followed the bursting of the dot-com bubble a decade ago.

“We expect compensation to be down dramatically this year,” she wrote in a recent report. She predicts the American banking industry will lay off 40,000 to 80,000 employees, or as many as 1 in 10 of its workers.

That may be extreme, but Ms. Whitney argues that the boom years are not coming back anytime soon. As both consumers and companies cut back on debt, and financial reform rules put the brakes on profitable niches like derivatives and proprietary trading, the engines of earnings growth for the last decade will continue to sputter.

By NELSON D. SCHWARTZ

Inside the great investment houses on Wall Street, business has taken a surprising turn — downward.

Even after taxpayer bailouts restored bankers’ profits and pay, the great Wall Street money machine is decelerating. Big financial institutions, including commercial banks, are still making a lot of money. But given unease in the financial markets and the economy, brokerages and investment banks are not making nearly as much as their executives, employees and investors had hoped.

After an unusually sharp slowdown in trading this summer, analysts are rethinking their profit forecasts for 2010.

The activities at the heart of what Wall Street does — selling and trading stocks and bonds, and advising on mergers — are running at levels well below where they were at this point last year, said Meredith Whitney, a bank analyst who was among the first to warn of the subprime mortgage disaster and its impact on big banks.

Worldwide, the number of stock offerings is down 15 percent from this time last year, while bond issuance is off 25 percent, according to Capital IQ, a research firm. Based on these trends, Ms. Whitney predicts that annual revenue from Wall Street’s main businesses will drop 25 percent, to around $42 billion in 2010, from $56 billion last year.

While the numbers will not be known until after the third quarter ends and financial companies begin reporting earnings in October, the pace of trading this summer was slow even by normal summer standards. Trading in shares listed on the New York Stock Exchange was down by 11 percent in July from 2009 levels, and August volume was off nearly 30 percent.

“What’s happened in the third quarter is that after a very slow summer, people expected things to come back,” said Ms. Whitney. “But they haven’t, and the inactivity is really squeezing everyone.”

The downward slide on Wall Street parallels a similar shift in the broader economy, which has slowed considerably since showing signs of a nascent recovery this spring. And if banks come under pressure, all but the safest borrowers may struggle to get loans.

With less than two weeks to go in the third quarter, companies will be hard-pressed to fulfill earlier, more optimistic expectations.

“It’s like the marathon: if you’re five miles behind, you can’t make that up in the last 10 minutes of the race,” said David H. Ellison, president of FBR Fund Advisers, a money management firm that specializes in financial companies. Many banks are barely scraping by in traditional Wall Street business.

As a result, executives, portfolio managers and analysts say that even the mighty Goldman Sachs, which posted a profit every day for the first three months of the year, is unlikely to deliver the kind of profit growth that investors have come to expect.

Keith Horowitz, a bank analyst at Citigroup, said he expected Goldman Sachs to earn $7.8 billion in 2010, a 35 percent decline from the $12.1 billion it made last year.

The drop in trading translates into lower commissions for brokerage firms, as well as a weaker environment for underwriting initial public offerings and other stock issues, traditionally a highly lucrative niche.

Banks are also scaling back on making bets with their own money — known as proprietary trading — another huge profit source in recent years that will soon be forbidden under terms of the financial reform legislation passed by Congress this summer.

Indeed, analysts have finally started to bring their forecasts in line with the new reality. On Sept. 12, Mr. Horowitz reduced his estimates for third-quarter profits at Goldman and Morgan Stanley.

Mr. Horowitz had predicted Goldman would make $1.75 billion in the third quarter, or $3 a share; he now expects Goldman’s profit to total $1.34 billion, or $2.30 a share. For Morgan Stanley, his revision was even steeper, with earnings expectations revised downward to $140 million, or 10 cents a share, from $726 million, or 53 cents a share.

Mr. Horowitz’s estimates are considerably lower than the consensus among analysts who track the two companies. If the other analysts revise their estimates closer to his, they would put pressure on the shares.

One of the rare bright spots for Wall Street recently has been the issuance of junk bonds, as ultra-low interest rates encourage investors to seek out riskier debt that carries a higher yield. But that will not be enough to offset the weakness elsewhere, said one top Wall Street executive who insisted on anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly for his company, and because final numbers would not be tallied until the end of the month.

To make matters worse, he said, many Wall Street firms increased their work forces in the first half of the year, before the mood shifted and worries of a double-dip recession arose. If activity remains anemic, firms could soon begin cutting jobs again.

“I think the summer was horrible for everyone, and no one expected it to be as bad as it was,” he said. “It’s coming back a little bit in September but nowhere near enough to make up for what happened in July and August.”

The profit picture is brighter for diversified companies like JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America, which have larger commercial and retail banking operations in addition to their Wall Street units, but some analysts say earnings expectations for them could come down as well.

“Estimates still seem a little high, and the revenue story for all the banks is not a good one,” said Ed Najarian, who tracks the banking sector for ISI, a New York research firm.

With interest rates plunging, banks are making less off their interest-earning assets like government bonds and other ultra-safe securities. At the same time, demand for new loans remains weak.

One wild card will be the credit card portfolios at major banks like JPMorgan, Bank of America and Citigroup. As delinquencies ease, Mr. Najarian said, credit losses are likely to decline. That trend helped earnings at JPMorgan in the second quarter, and could be crucial again in the third quarter.

Ms. Whitney says the gloomy short-term predictions foreshadow a series of lean years in the broader financial services industry.

Indeed, she said the Street faced a “resizing” not seen since the cutbacks that followed the bursting of the dot-com bubble a decade ago.

“We expect compensation to be down dramatically this year,” she wrote in a recent report. She predicts the American banking industry will lay off 40,000 to 80,000 employees, or as many as 1 in 10 of its workers.

That may be extreme, but Ms. Whitney argues that the boom years are not coming back anytime soon. As both consumers and companies cut back on debt, and financial reform rules put the brakes on profitable niches like derivatives and proprietary trading, the engines of earnings growth for the last decade will continue to sputter.

19/09 Just Manic Enough: Seeking Perfect Entrepreneurs

Matthew Cavanaugh for The New York Times

Matthew Cavanaugh for The New York TimesSeth Priebatsch’s passionate pitch won over investors for his latest start-up.

September 18, 2010

By DAVID SEGAL

Cambridge, Mass.

IMAGINE you are a venture capitalist. One day a man comes to you and says, “I want to build the game layer on top of the world.”

Matthew Cavanaugh for The New York Times

Matthew Cavanaugh for The New York Times“You need to suspend disbelief to start a company,” says the investor Paul Maeder. “So many people will tell you that what you’re doing can’t be done.”

You don’t know what “the game layer” is, let alone whether it should be built atop the world. But he has a passionate speech about a business plan, conceived when he was a college freshman, that he says will change the planet — making it more entertaining, more engaging, and giving humans a new way to interact with businesses and one another.

If you give him $750,000, he says, you can have a stake in what he believes will be a $1-billion-a-year company.

Interested? Before you answer, consider that the man displays many of the symptoms of a person having what psychologists call a hypomanic episode. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual — the occupation’s bible of mental disorders — these symptoms include grandiosity, an elevated and expansive mood, racing thoughts and little need for sleep.

“Elevated” hardly describes this guy. To keep the pace of his thoughts and conversation at manageable levels, he runs on a track every morning until he literally collapses. He can work 96 hours in a row. He plans to live in his office, crashing in a sleeping bag. He describes anything that distracts him and his future colleagues, even for minutes, as “evil.”

He is 21 years old.

So, what do you give this guy — a big check or the phone number of a really good shrink? If he is Seth Priebatsch and you are Highland Capital Partners, a venture capital firm in Lexington, Mass., the answer is a big check.

But this thought exercise hints at a truth: a thin line separates the temperament of a promising entrepreneur from a person who could use, as they say in psychiatry, a little help. Academics and hiring consultants say that many successful entrepreneurs have qualities and quirks that, if poured into their psyches in greater ratios, would qualify as full-on mental illness.

Which is not to suggest that entrepreneurs like Seth Priebatsch (pronounced PREE-batch) are crazy. It would be more accurate to describe them as just crazy enough.

“It’s about degrees,” says John D. Gartner, a psychologist and author of “The Hypomanic Edge.” “If you’re manic, you think you’re Jesus. If you’re hypomanic, you think you are God’s gift to technology investing.”

The attributes that make great entrepreneurs, the experts say, are common in certain manias, though in milder forms and harnessed in ways that are hugely productive. Instead of recklessness, the entrepreneur loves risk. Instead of delusions, the entrepreneur imagines a product that sounds so compelling that it inspires people to bet their careers, or a lot of money, on something that doesn’t exist and may never sell.

So venture capitalists spend a lot of time plumbing the psyches of the people in whom they might invest. It’s not so much about separating the loonies from the slightly manic. It’s more about determining which hypomanics are too arrogant and obnoxious — traits common to the type — and which have some humanity and interpersonal skills, always helpful for recruiting talent and raising money.

Some V.C.’s have personality tests to help them weed out the former. Others emphasize their toleration of mild forms of mania, if only because starting a business is, on its face, a little nuts.

“You need to suspend disbelief to start a company, because so many people will tell you that what you’re doing can’t be done, and if it could be done, someone would have done it already,” says Paul Maeder, a general partner at Highland Capital. “There are six billion human beings on this planet, we’ve been around for hundreds of thousands of years, we’re a couple hundred years into the industrial revolution — and nobody has done what you want to do? It’s kind of crazy.”

ON a recent Saturday evening, Seth Priebatsch is sitting in his office/bedroom in the 26,000-square-foot space that houses Scvngr (pronounced “scavenger”), which he founded in early 2009. Dozens of toy race cars fill a bookshelf on one wall; the other is covered with lists and drawings. The sofa where he crashes in his sleeping bag lies between the two.

He will explain the genesis of Scvngr, and offer a sort of guided tour of his mind, while sitting on a stool in his bare feet, wearing jeans and a Princeton T-shirt. A pair of Oakley sunglasses are perched, as they nearly always are, atop his head — part talisman, part personal branding.

He is lean, smiley and partial to the word “awesome,” which he uses as a noun — as in “an extra dose of awesome.” He speaks quickly and with what sounds like a Canadian accent, which seems odd because he was raised in Boston.

He first pitched Scvngr as a freshman at Princeton, to a professor linked to an annual business plan contest open to undergraduates and graduates. “I told him I wanted to build the game layer on top of the world,” Mr. Priebatsch recalls. “And he didn’t say, ‘You’re insane.’ So I said, ‘And I want everyone in the world to help me build it.’”

Scvngr won first prize, which came with $5,000 and emboldened him to apply to a seed financing company, DreamIt Ventures, which gave him $35,000. The victory also caught the eye of a venture capitalist, Peter Bell of Highland Capital, who read about Mr. Priebatsch’s prize while surfing the Web one night. Mr. Bell popped off an e-mail.

“It was Saturday night, pretty late,” Mr. Bell recalls. “I said, ‘If you ever come to Boston, I’d love to meet you.’”

Mr. Priebatsch replied immediately: he’d decided to drop out of Princeton and move to Boston. The university would be around a long time, he reasoned, but the moment to start Scvngr was fleeting and couldn’t wait a few weeks, let alone three years.

So, what is this potentially globe-altering enterprise?

“Scvngr is a game that you play on your phone, and playing Scvngr is incredibly easy,” he begins.

The game allows you to compete and win rewards at stores, gyms, theaters, museums and so on. A Mexican restaurant, for instance, might offer half off your next soda if you fold the tin foil on your burrito into origami, then snap a picture of it.

If this sounds like little more than a gimmicky way to lure in consumers, well, you haven’t listened to Mr. Priebatsch long enough.

“We play games all the time, right?” he says. “School is a game. It’s just a very badly designed game.” American Express cards, with their escalating status, from green, to gold to black — they are a game. So are frequent-flier miles.

“But game dynamics aren’t consciously leveraged in any meaningful way, and Scvngr does that.”

This, apparently, has enormous implications. “If we can bring game dynamics to the world, the world will be more fun, more rewarding, we’ll be more connected to our friends, people will change their behavior to be better. But if this is going to work it has to be something that anyone can play and that everyone can build.”

This, he says, is the key: Scvngr is both a game and a game platform. Anyone can create a Scvngr challenge, free, using four default games or tools the company offers. There are now 20 million Scvngr challenges in the United States, according to the company, most of which are simple tasks, like “stand in this spot and say something.”

In addition, about 1,000 companies and organizations — including the New England Patriots, Zipcar, Sony and Warner Brothers — pay Scvngr to create and manage their challenges.

“The last decade was the decade where the social framework was built,” he says — most successfully by Facebook. “The next decade will be the decade of games.”

Judging this pitch by reading it, as opposed to hearing it in person, is like appraising a song based solely on its lyrics. Mr. Priebatsch describes Scvngr and the future it portends with burbling fluency, as if it were a country he has visited and one that you must see. He is especially good at giving “the game layer” an aura of inevitability.

It is hardly clear, though, that such a layer will catch on or, if it does, whether Scvngr will be the company to build it. The field of location-based tech games is crowded, and include standouts like Foursquare and Gowalla.

The particulars of Scvngr seem nitpickable, too. The game’s points will earn you whatever goodie is offered on the spot, but there is nothing else you can do with them. And some users have found Scvngr’s challenges to be pretty lame. More than a few of the contests seem like barely veiled marketing ploys — like retailers that “challenge” you to come up with three words that describe the store.

Reviews so far have split the crowd. As of last week, a third of the roughly 1,000 people who had weighed in on the latest version of Scvngr in the iPhone’s App Store gave it the highest rating and one-third gave it the lowest.

“Not relevant to having fun,” read one review.

But Mr. Priebatsch’s pitch has worked, at least by the standards of start-ups, most of which die in the blueprint phase. Part of the reason could be pinned on the investing and tech world’s raging case of Next Zuckerberg Syndrome — the urge to find another Mark Zuckerberg before he starts another Facebook.

But nobody inspires N.Z.S. without a promising idea, intelligence and a lot of charisma. Scvngr today has 60 employees, many of them veterans of very successful tech start-ups. As of December of last year, it also had $4 million from Google Ventures.

Any list of the qualities that have netted all this talent and money should include Mr. Priebatsch’s quasirobotic work ethic. He does not socialize. He no longer reads books, nor does he watch TV or movies. He works from 8 a.m. until 10 p.m., seven days a week. He was reluctant to have a photographer visit for this article because he worried that it might distract employees.

Doesn’t he miss going to bars, just hanging out, being 21? Here’s where Mr. Priebatsch starts to sound like a teenage Vulcan.

“I had friends at Princeton; I’m sure it’d be fun to see them,” he says. “But I know that what I’m going after is huge and others are going after it, and if they’re not, they’re making a mistake. But other people will figure it out, and every minute that I’m not working on it is a minute when they’re making progress and I’m not. And that is just not O.K.”

THE hypomanic temperament is, of course, not limited to entrepreneurs. It’s found in politics (Theodore Roosevelt) the military (George S. Patton), Hollywood (the studio head David O. Selznick) and virtually any field where outsize risks yield enormous rewards.

But the business world has contributed more than its share of hypomanics, particularly the abusive, ornery kind. The most colorful of the breed was arguably Henry Ford.

“He epitomizes the unhinged, entrepreneurial spirit,” says Douglas G. Brinkley, a history professor at Rice University and author of “Wheels for the World,” a book about Mr. Ford and his company. “He became monomaniacal in his belief that the internal combustion engine should be fueled by gas, at a time when everything was electric, and nobody thought you could put gas on a hot motor.”

Mr. Ford could be both charmer and ruthless jerk. When he visited rural America to extol the horseless carriage, listeners were often left hoping that he would run for president. With employees, on the other hand, he was an autocrat who never brooked dissent. He clung so stubbornly to his vision — black cars, and only black cars, for the masses — that the company almost went bust when rivals like General Motors started offering more choices.

Nearly all conversations about contemporary hypomanics start with the Apple chief executive, Steven P. Jobs. Like Mr. Ford, he is a pitchman extraordinaire with a vaguely messianic streak, and, like Mr. Ford, he can anticipate what people will want before they even know they want it.

Mr. Jobs is also routinely described as a despot and control freak with a terrifying temper, says Leander Kahney, author of “Inside Steve’s Brain.”

“Even the prospect of a chewing out by Steve Jobs makes people work 90 hours a week,” says Mr. Kahney. He treats employees as tools, Mr. Kahney went on, as a means to an end, with the end defined as a universe of Apple products and services that are tailored precisely to his specifications.

“I would argue that Jobs has used his control freakery to advantage,” Mr. Kahney says. “The hallmark of Apple is the way it controls the entire user experience — the ads, the stores, the iPods. Nothing is left to chance. That comes from Steve Jobs.”

Scholars in organizational studies tend to divide the world into “transformational leaders” (the group that hypomanics are bunched into, of course) and “transactional leaders,” who are essentially even-keeled managers, grown-ups who know how to delegate, listen and set achievable goals.

Both types of leaders need to rally employees to their cause, but entrepreneurs must recruit and galvanize when a company is little more than a whisper of a big idea. Shouting “To the ramparts!” with no ramparts in sight takes a kind of irrational self-confidence, which is perfectly acceptable, though it can also tilt into egomania, which is usually not.

“We have a grid personality scorecard, across 10 or 12 dimensions, attributes that are critical to success,” says Michael A. Greeley, a general partner at Flybridge Capital Partners in Boston.

The goal is to spot the really erratic characters, whom Mr. Greeley calls “rail to rail”:

“One day they get up and their favorite color is pink. The next day, it’s green. I’ve worked with hypomanics, and where I think it can be quite insidious — people like this turn on colleagues quickly. An employee could be an incredible contributor, and then, after one mistake, they are out of the lifeboat.”

BEFORE Highland Capital invested in Scvngr, Peter Bell gave Seth Priebatsch’s life and résumé the vigorous frisking that is standard in the venture capital business.

Mr. Priebatsch was 19 at the time, which meant that he didn’t have a lot of former colleagues or bosses. What he did have, however, was a surprisingly long track record in business.

Scvngr is actually the third company that Mr. Priebatsch has founded. At the age of 12, with money from his parents, he started Giftopedia, a price-comparison shopping Web site. When he was in eighth grade, the company had eight employees — six in India, two in Russia.

Nobody who worked for him ever asked him his age, and he never volunteered it. “I wouldn’t say that I kept my age a secret,” he says. “I just never offered that information. Nobody knows how old you are on the Internet.”

All communications were handled via e-mail and Skype, often while he was typing on a laptop while sitting in class. For a long time, his teachers thought that he was simply taking copious notes, but he was actually sending instructions overseas with a wireless connection.

“One day, I forgot to hit the mute button on my laptop and it started ringing during French class,” he recalls. The Giftopedia server was down that day, and it was a crisis.

“I got up and told my teacher, ‘I’m really sorry, but I have to take this call.’ ”

Giftopedia was profitable, but a little late to the field, Mr. Priebatsch says. Ultimately, he sold the domain name for five figures and, at 17, founded PostcardTech, which created and mailed out promotional mini-CDs on behalf of tourist destinations and universities. For that company, he rented part of a factory in China, which, he said, was time-consuming but surprisingly easy and didn’t even require a trip to Asia.

Mr. Priebatsch handed PostcardTech off to some friends, who did little with it, and the company has since folded. But it left Mr. Priebatsch with a chunk of money — he won’t say how large — that he has since invested in Scvngr.

Dr. Gartner, the author and psychologist, says he believes that hypomanics come by their disposition genetically. But it is hard to tease out what Norman and Suzanne Priebatsch — a biotech entrepreneur and a financial adviser at SmithBarney, respectively — bequeathed through their DNA and what they instilled in Seth and his older sister, Daniella Priebatsch, as they grew up.

Because chez Priebatsch sounds like boot camp for the brain.

“With both my kids, my wife and I pushed them very hard,” says Norman Priebatsch, who is a native of South Africa. “Very invasive, very intrusive, doing things, planning things continuously.”

As a child, when Seth started to read along with his father — high-level math, physics and history books were the staples — the elder Mr. Priebatsch would often turn the books upside down, adding a degree of difficulty to the experience, and presumably some fun.

The upshot is that Seth can now read as quickly upside down as right-side up, something to keep in mind if you ever find yourself sitting across a desk from him.

“People assume that if you’ve got a sheet of paper in front of you that no one else can read it,” he says, “and that is false.”

Vacations, Seth says, made school seem relaxing. He and his sister were expected to research destinations — Istanbul, Shanghai and Rome, for instance — and then plan most of the itinerary down to the hour. On the trips, they would tour all day and night, leaving time for the children to upload photos to a laptop and type up a detailed account of everything they’d seen.

“We were the scribes of those trips; that was a requirement,” says Daniella, who now works on a sales team at Google. “Every detail — what it was like at the museum, people we met. Even the room number of the hotel, in case it was a good room and we ever came back.”

The rigor and intensity of Seth’s upbringing have left him with a peculiar combination of rarefied skills and mundane deficiencies. He is a gifted software engineer but a terrible driver. (“I hit things,” he says.) He’s perfectly at ease negotiating with V.C.’s, but has had just one girlfriend, a relationship that ended abruptly when someone asked how long they’d been dating.

“We answered simultaneously and she said six months and I said two weeks,” he recounts, sounding amused. “Two weeks earlier we’d had this conversation, and I said, ‘And so now we’re dating, correct?’ And she said yes.”

He shrugs.

“I thought I’d been really clear,” he says. “I find business relationships are easier. You have to sign a piece of paper.”

IN late 2008, as part of the investment process, Mr. Priebatsch had to visit Highland Capital’s offices and present his plan to the firm’s partners.

It went well, but there are still skeptics at the firm. Mr. Maeder of Highland still wonders whether Scvngr is the scaffolding of a major business. At the same time, he regards the $750,000 investment as a bet on Mr. Priebatsch as much as a bet on his company.

“Seth has such a fertile mind; you just know that he’ll attract great people to the company,” he says, “and the ideas will continue to flow and morph until he finds something great.”

You also get the sense that Mr. Priebatsch won’t stop, even if Scvngr is a glorious triumph.

“I like winning,” he says. “I’m addicted to the act of winning, the process. When you are in the act of winning, everything is great. Once you’ve won, that’s boring. It’s cool, it’s better than having lost, but it’s boring.”

Great piles of money would not slow him down, either.

“I’m not anti-money,” he says. “I like nice bikes, I like nice computers. I like that money is a representation of success, but the actual entity itself is not interesting for me. There is little that I would want that I don’t have, and the things that I want money can’t buy.”

Like?

He doesn’t pause.

“I want to build the game layer on top of the world.”

Labels: Introduction

Entreprener

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)